Dietary sulfur is an essential component for cellular health. It is vital for the proper formation of proteins and enzymes, and also serves as a vital cofactor in metabolic processes required to convert food into cellular energy and components. Inadequate intake of dietary sulfur results in dysfunction and disease.

- Sulfur is vital for enzyme and protein production as well as important metabolic processes

- Sulfur is also essential for the production of detoxifying compounds and antioxidants

- Sulfur content in food is decreasing due to soil depletion

- Inadequate intake of dietary sulfur results in dysfunction and disease

Tell me more

Strike a match, and you see the tip of the match quickly ignite in a burst of energy and you quickly recognize a very distinct and familiar odor. That specific odor comes from the element sulfur, that is responsible for the ability of matches to ignite. But did you know that the same element is also vital for many of the biochemical processes in the human body? Without sulfur, the “spark of life” would not be possible. It is the sixth most abundant macromineral found in breast milk, and as a percentage of body weight it is the third most abundant mineral found in adults.1

Our bodies need sulfur in forms that are different from the sulfur on a match head. Sulfur gets chemically incorporated into larger molecules and amino acids that can be found in certain foods, hard water, and supplements. These are the forms that your body recognizes and knows how to incorporate into its complex biochemical processes. Some of the most common dietary forms of sulfur include methionine, methylsulfonylmethane (MSM), L-taurine, sulforaphane, N-acetyl-L-cysteine, thiamine (Vitamin B1), and biotin.1,2

Where do we get sulfur in our diets?

Rich dietary sources of sulfur include healthy vegetables that we sometimes associate with sulfur-like odors such as cabbage, garlic, cauliflower, broccoli, leeks, Brussels sprouts, asparagus, nuts, beans, kale, radishes, and spinach.1,3,4 Broccoli is actually one of the most potent sources of sulforaphane that has been widely studied and shown to have potent health benefits.5–7 Foods high in protein contain sulfur, but amounts vary based on the types of amino acids that compose the proteins. Shellfish like lobster, crab, and scallops are excellent sources of sulfur. Eggs are also a good source of sulfur, however many people eat fewer eggs due to concerns about cholesterol.

People may not be getting adequate sulfur from their normal diets and this may contribute to the development of some diseases.3 Sulfur is typically better absorbed and utilized when it comes from animal protein sources as compared to vegetables however there are exceptions.1 Many crops are now grown in soil that has been depleted of sulfur over time so the content found in our food is lower than in the past.8,9 Transporting, processing, cooking, and washing food can reduce the levels of sulfur compounds found in food, causing them to become nutritionally deficient.8,9

Why does the body need sulfur?

Sulfur is required for production of DNA, insulin, hormones, enzymes, antibodies, neurotransmitters, amino acids (building blocks of proteins), collagen, connective tissues, and much more. It is also essential for the production of detoxifying compounds and antioxidants like glutathione, making it an essential component for the metabolism of many medications, hormones, metabolic waste products, free radicals, and dietary/environmental toxins.1 N-acetyl-L-cysteine is used universally in hospitals around the world as a remedy to protect the liver following poisonings and overdoses from things like acetaminophen (active ingredient in Tylenol®).10,11

The sulfur-containing amino acid cysteine is also an essential component of many proteins and polypeptides because of its ability to form “disulfide bonds.” These very strong bonds help determine a protein’s shape and function while providing biochemical stability.12 Interestingly, disulfide bonds are more common in extracellular proteins (extracellular = outside of the cell) such as insulin and albumin, while they are generally not found in intercellular proteins (intracellular = inside of the cell) such as hemoglobin and myoglobin.12

N-acetyl-L-cysteine, L-taurine, sulforaphane, and MSM have all been shown to have a variety of additional health benefits related to the sulfur they contain.13–17 They play a role in providing cell membranes with the fluidity they need for proper signaling, dividing, and many more functions.18 The sulfur in N-acetyl-L-cysteine is even known to help break up mucous secretions in lungs, and is sometimes used in treating conditions like cystic fibrosis.10,11,19

Proprietary Blend Nutritional Supplements provide natural sources of sulfur

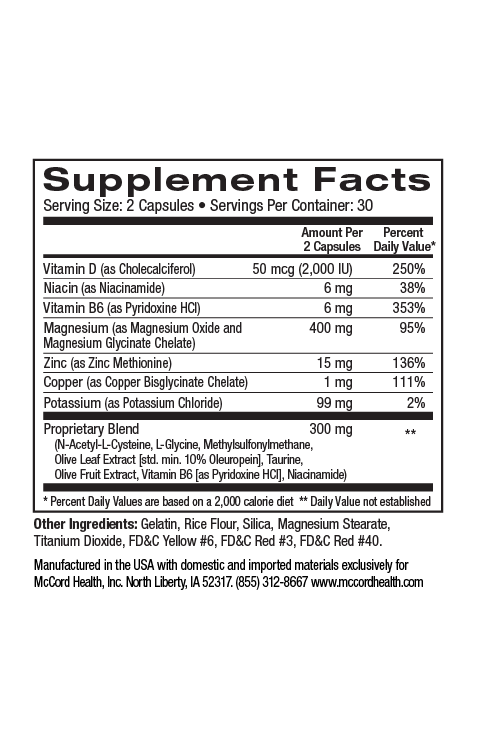

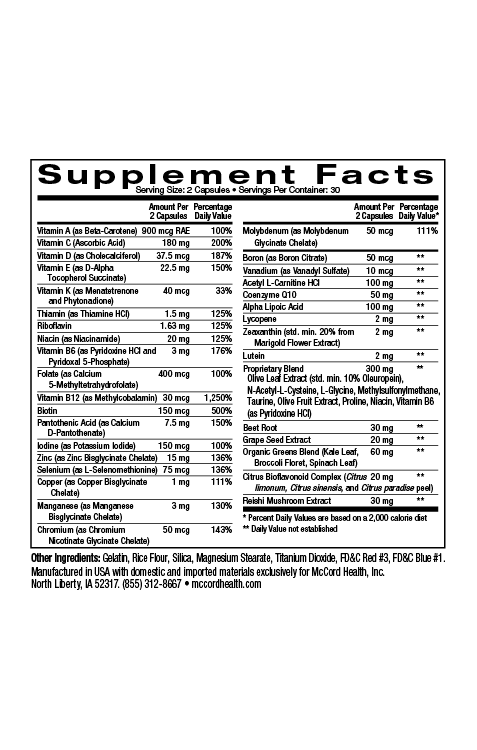

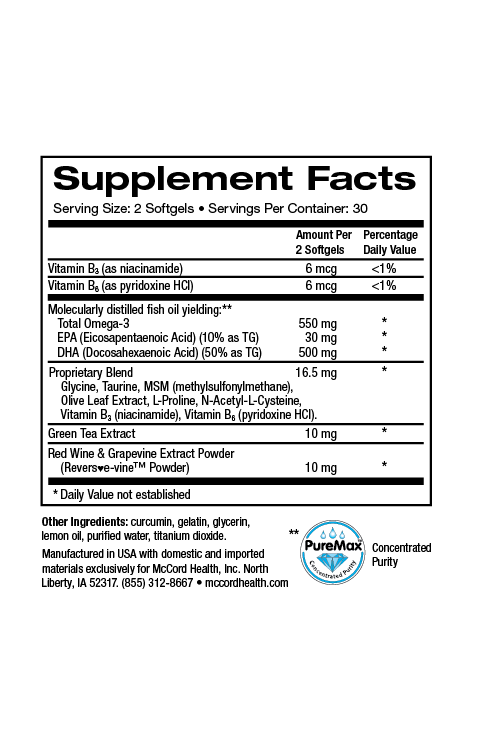

The Proprietary Blend nutritional supplements were designed to provide your body with the sulfur sources that it needs to function properly. In fact, N-acetyl-L-cysteine, L-taurine and MSM are combined with hydroxytyrosol from olives plus B vitamins to create the patented formula found in all McCord Research Proprietary Blend products.

References

- Parcell S. Sulfur in human nutrition and applications in medicine. Altern Med Rev. 2002;7(1):22–44.

- Brosnan JT, Brosnan ME. The Sulfur-Containing Amino Acids: An Overview. J Nutr. 2006;136(6):1636S–1640.

- Nimni ME, Han B, Cordoba F. Are we getting enough sulfur in our diet? Nutr Metab (Lond). 2007;4:24.

- Higdon J V, Delage B, Williams DE, Dashwood RH. Cruciferous vegetables and human cancer risk: epidemiologic evidence and mechanistic basis. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55(3):224–36.

- Houghton C a, Fassett RG, Coombes JS. Sulforaphane: translational research from laboratory bench to clinic. Nutr Rev. 2013;71(11):709–26.

- Shapiro TA, Fahey JW, Dinkova-Kostova AT, et al. Safety, tolerance, and metabolism of broccoli sprout glucosinolates and isothiocyanates: a clinical phase I study. Nutr Cancer. 2006;55(1):53–62.

- Yanaka A, Fahey JW, Fukumoto A, et al. Dietary sulforaphane-rich broccoli sprouts reduce colonization and attenuate gastritis in Helicobacter pylori-infected mice and humans. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2009;2(4):353–60.

- Lester GE. Organic versus Conventionally Grown Produce: Quality Differences, and Guidelines for Comparison Studies. HortScience. 2006;41(2):296–300.

- Hounsome N, Hounsome B, Tomos D, Edwards-Jones G. Plant metabolites and nutritional quality of vegetables. J Food Sci. 2008;73(4):R48–65.

- Atkuri KR, Mantovani JJ, Herzenberg L a, Herzenberg L a. N-Acetylcysteine–a safe antidote for cysteine/glutathione deficiency. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7(4):355–9.

- Kelly GS. Clinical applications of N-acetylcysteine. Altern Med Rev. 1998;3(2):114–27.

- Butera D, Cook KM, Chiu J, Wong JWH, Hogg PJ. Control of blood proteins by functional disulfide bonds. Blood. 2014;123(13):2000–7.

- Johansson NL, Pavia CS, Chiao JW. Growth inhibition of a spectrum of bacterial and fungal pathogens by sulforaphane, an isothiocyanate product found in broccoli and other cruciferous vegetables. Planta Med. 2008;74(7):747–50.

- Kim YH, Kim DH, Lim H, Baek D-Y, Shin H-K, Kim J-K. The anti-inflammatory effects of methylsulfonylmethane on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in murine macrophages. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32(4):651–6.

- Kim LS, Axelrod LJ, Howard P, Buratovich N, Waters RF. Efficacy of methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) in osteoarthritis pain of the knee: a pilot clinical trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(3):286–94.

- El Idrissi A, Shen CH, L’amoreaux WJ. Neuroprotective role of taurine during aging. Amino Acids. 2013;45(4):735–50.

- Sturman JA, Hepner GW, Hofmann AF, Thomas PJ. Metabolism of [35S]taurine in man. J Nutr. 1975;105(9):1206–14.

- Abebe W, Mozaffari MS. Role of taurine in the vasculature: an overview of experimental and human studies. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;1(3):293–311.

- Townsend DM, Tew KD, Tapiero H. The importance of glutathione in human disease. Biomed Pharmacother. 2003;57:145–155.

Disclaimer: These statements have not been reviewed by the FDA. Pinnaclife products are dietary supplements and are not intended to treat, cure, or prevent any disease. The decision to use these products should be discussed with a trusted healthcare provider. The authors and the publisher of this work have made every effort to use sources believed to be reliable to provide information that is accurate and compatible with the standards generally accepted at the time of publication. The authors and the publisher shall not be liable for any special, consequential, or exemplary damages resulting, in whole or in part, from the readers’ use of, or reliance on, the information contained in this article. The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.