Antibiotic use, especially in childhood, has been linked to obesity later in life. Overuse of broad-spectrum antibiotics causes disruptions in the intestinal microbiome that influences metabolism. You can protect, maintain and restore probiotic bacteria with prebiotic fiber when using antibiotics.

Antibiotic Use, Gut Bacteria, and the Link to Obesity

- Most people have or will use antibiotics at some point in their life

- Use of antibiotics appears to be linked to increased risk of obesity

- The composition of intestinal bacteria can impact metabolism and contribute to obesity

- Antibiotics can disrupt the healthy bacteria living in and on your body

- Restoring and maintaining proper intestinal bacteria is important for people who have used antibiotics

- Boosting your immune system is your best defense against illness and the need for antibiotics

Tell me more!

It’s probably safe to say that most of us have at least one childhood memory that involves choking down a liquid antibiotic that even a spoonful of sugar couldn’t help. Despite all of the attempts to mask the taste with bubble gum, cherry, and grape flavors, our sophisticated palates told us that this stuff was “icky!”

Of course, we eventually got it down and hopefully within a couple of days we were feeling much better – once again reminded that mom and dad know best.

Overuse of Antibiotics

We know that antibiotics are important tools for keeping us healthy and stopping the spread of disease, however it is becoming more apparent that the overuse of these types of medications may have more negative consequences than previously thought.

Some of the negative consequences like antibiotic resistance were somewhat anticipated while other side effects may catch some people by surprise. For example, a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Pediatrics concluded that repeated exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics within the first 24 months of life significantly increases a child’s likelihood of becoming obese.1

The results of this study are troubling considering the high rates and negative health effects of obesity plus reports from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) showing that children aged 0-2 have the highest rates of antibiotic use of any age group.

Another study indicated that broad-spectrum antibiotics are being used more often than narrow-spectrum antibiotics in children and adolescents, with a 143% increase in use between 2000 and 2010.2

Even more alarming is that almost 80% of antibiotic prescriptions for acute respiratory illnesses were unnecessary based on accepted practice guidelines.3

How could antibiotics contribute to obesity?

The authors of the JAMA-Pediatrics study concluded that the link between broad-spectrum antibiotic use during childhood and obesity is most likely a result of the disruption of healthy intestinal bacteria (probiotics) caused by antibiotics.

This finding is supported by additional research as well. Countless studies have confirmed the importance of intestinal bacteria in maintaining your health with several studies linking specific intestinal microflora to obesity and other metabolic disorders.4–9

While the JAMA-Pediatrics study specifically looked at antibiotic use in children, and childhood obesity, it is important to realize that these findings likely apply to adults as well as children. It is well established that intestinal bacteria play an important role in people of all ages, and antibiotics can disrupt the balance. This study just helps to highlight the important role our beneficial bacteria play in our overall health, from infancy through adulthood.

Maintaining a Healthy Intestinal Microbiome

Healthy intestines require a proper balance between beneficial bacteria and harmful (pathogenic) bacteria.10 Certain foods and medications disrupt this balance causing negative effects throughout the entire body.11

When you take a broad-spectrum antibiotic, it not only kills the bacteria making you sick, but can also kill your beneficial intestinal bacteria that keep you healthy. This is one of the reasons that every antibiotic is capable of causing upset stomach or diarrhea and also why your healthcare provider may recommend using a prebiotic and/or probiotic supplement when taking antibiotics.

Prebiotics and Probiotics: What's the Difference?

The term “prebiotic” is used to describe the food that “probiotic” bacteria eat. When you incorporate prebiotics into your diet, they naturally support and maintain the balance of healthy bacteria in your intestines by providing them with an ample food supply.

Proprietary Blend DigestiveHealth contains a type of soluble prebiotic fiber that has been shown to selectively increase the amount of beneficial probiotic bacteria like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium in your intestines and may function as a remedy to antibiotic associated imbalances.12,13 When the beneficial bacteria are thriving, they crowd out the harmful bacteria that make you sick, cause inflammation, and are linked to obesity.

In contrast to prebiotics, “probiotic” supplements contain actual bacteria and are intended to restore levels of healthy bacteria by ingesting large quantities of living organisms. Their effectiveness relies on a high concentration of viable (living) bacteria surviving long enough to make it into your large intestines, where they only flourish if there is enough prebiotic food available to support them.

What this means is that the probiotic bacteria must survive the manufacturing process, shipment, storage, stomach acid, and digestive enzymes – all to get to the areas of the intestines where they are needed.

Many commercial sources of probiotics require refrigeration to prevent the bacteria from dying while the product is in transit or sits on a shelf. Even when stored properly, they generally lose potency quickly, giving them a short effective shelf life. You may even see some probiotics that are "enteric coated" to protect the bacteria from stomach acid. Even when manufactured and stored properly, they generally lose potency quickly, giving them a very short shelf life. You'll also notice that most refrigerated and/or enteric coated probiotic products come with a significant price tag. Some food sources that advertise about probiotics, such as frozen yogurt, actually contain little to no viable probiotics due to freezing, heating, manufacturing processes, or bacteria-killing preservatives.

Proprietary Blend DigestiveHealth does not contain (or need to contain) any living bacteria, so it does not require refrigeration and will not lose potency on the shelf or after being frozen or heated.14,15 Using Proprietary Blend DigestiveHealth daily can help you maintain a healthy balance of probiotic bacteria in your intestines.16–18

You don't need antibiotics if you don't get sick

There's no doubt that antibiotics play an important role in keeping us healthy, and you should follow your personal health care provider's recommendations when it comes to using them. However, the best thing you can do to avoid needing to use antibiotics is to be proactive in keeping yourself healthy.

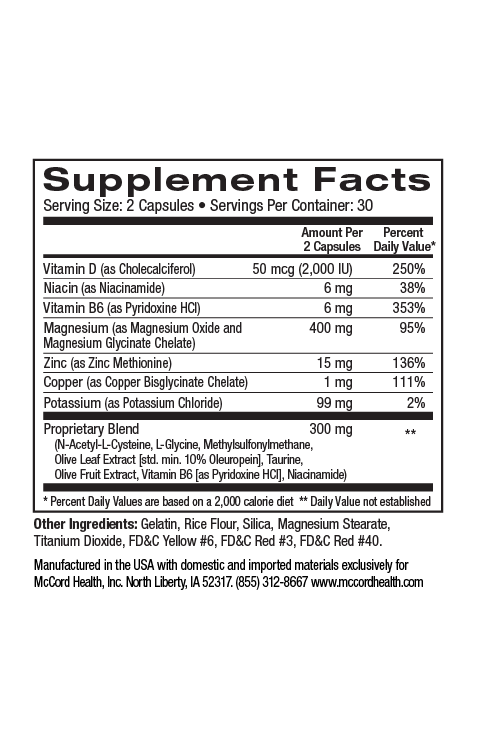

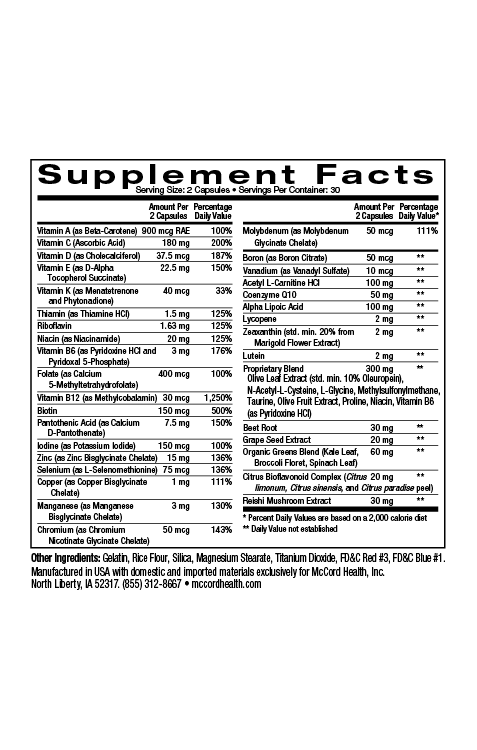

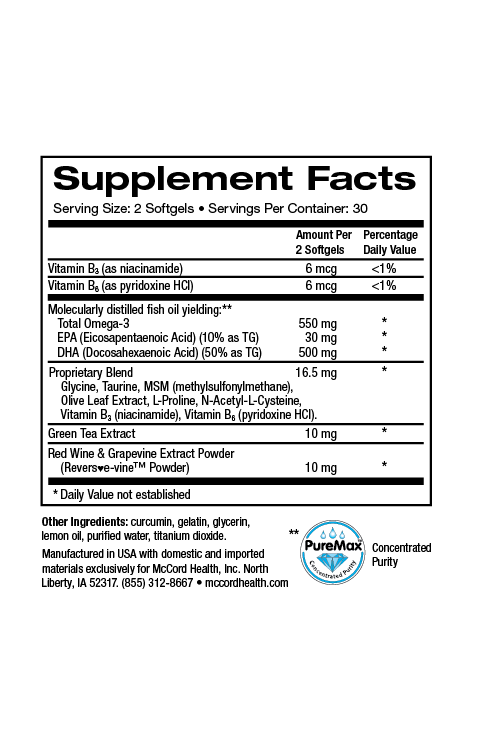

Always try to live a healthy lifestyle that includes physical activity, a healthy diet, adequate sleep, hydration, stress reduction, and avoiding drugs and alcohol. You can also add additional McCord Research Proprietary Blend Supplements like ImmuneHealth and TotalHealth MultiVitamin to help provide your body and immune system with vital antioxidants, vitamins, minerals and other nutrients to improve your chances of staying healthy. After all, the best way to remedy the side effects from antibiotics is to avoid needing to use them in the first place!

References

- Bailey LC, Forrest CB, Zhang P, Richards TM, Livshits A, DeRusso PA. Association of Antibiotics in Infancy With Early Childhood Obesity. JAMA Pediatr. 2014.

- Lee GC, Reveles KR, Attridge RT, et al. Outpatient antibiotic prescribing in the United States: 2000 to 2010. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):96.

- Scott JG, Cohen D, DiCicco-Bloom B, Orzano AJ, Jaen CR, Crabtree BF. Antibiotic use in acute respiratory infections and the ways patients pressure physicians for a prescription. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(10):853–8.

- Culligan EP, Hill C, Sleator RD. Probiotics and gastrointestinal disease: successes, problems and future prospects. Gut Pathog. 2009;1(1):19.

- Douglas LC, Sanders ME. Probiotics and prebiotics in dietetics practice. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(3):510–21.

- Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M. Obesity, diabetes, and gut microbiota: the hygiene hypothesis expanded? Diabetes Care. 2010;33(10):2277–84.

- Lakhan SE, Kirchgessner A. Gut inflammation in chronic fatigue syndrome. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2010;7:79.

- Fasano A, Shea-Donohue T. Mechanisms of disease: the role of intestinal barrier function in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal autoimmune diseases. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2(9):416–22.

- Shoaie S, Nielsen J. Elucidating the interactions between the human gut microbiota and its host through metabolic modeling. Front Genet. 2014;5:86.

- Heintz C, Mair W. You are what you host: microbiome modulation of the aging process. Cell. 2014;156(3):408–11.

- David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505(7484):559–63.

- Ukhanova M, Culpepper T, Baer D, et al. Gut microbiota correlates with energy gain from dietary fibre and appears to be associated with acute and chronic intestinal diseases. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(Suppl. 4):62–6.

- Fastinger ND, Karr-Lilienthal LK, Spears JK, et al. A Novel Resistant Maltodextrin Alters Gastrointestinal Tolerance Factors, Fecal Characteristics, and Fecal Microbiota in Healthy Adult Humans. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27(2):356–366.

- Goda T, Kajiya Y, Suruga K, Tagami H, Livesey G. Availability, fermentability, and energy value of resistant maltodextrin: modeling of short-term indirect calorimetric measurements in healthy adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(6):1321–1330.

- Englyst HN, Cummings JH. Digestion of the polysaccharides of some cereal foods in the human small intestine. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;42(5):778–87.

- Kishimoto Y, Kanahori S, Sakano K, Ebihara S. The maximum single dose of resistant maltodextrin that does not cause diarrhea in humans. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2013;59(4):352–7.

- Brownawell AM, Caers W, Gibson GR, et al. Prebiotics and the health benefits of fiber: current regulatory status, future research, and goals. J Nutr. 2012;142(5):962–74.

- Flickinger EA, Wolf BW, Garleb KA, et al. Glucose-Based Oligosaccharides Exhibit Different In Vitro Fermentation Patterns and Affect In Vivo Apparent Nutrient Digestibility and Microbial Populations in Dogs. Nutr Metab. 2000;(February):1267–1273.

Disclaimer: These statements have not been reviewed by the FDA. These products are dietary supplements and are not intended to treat, cure, or prevent any disease. The decision to use these products should be discussed with a trusted healthcare provider. The authors and the publisher of this work have made every effort to use sources believed to be reliable to provide information that is accurate and compatible with the standards generally accepted at the time of publication. The authors and the publisher shall not be liable for any special, consequential, or exemplary damages resulting, in whole or in part, from the readers’ use of, or reliance on, the information contained in this article. The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.